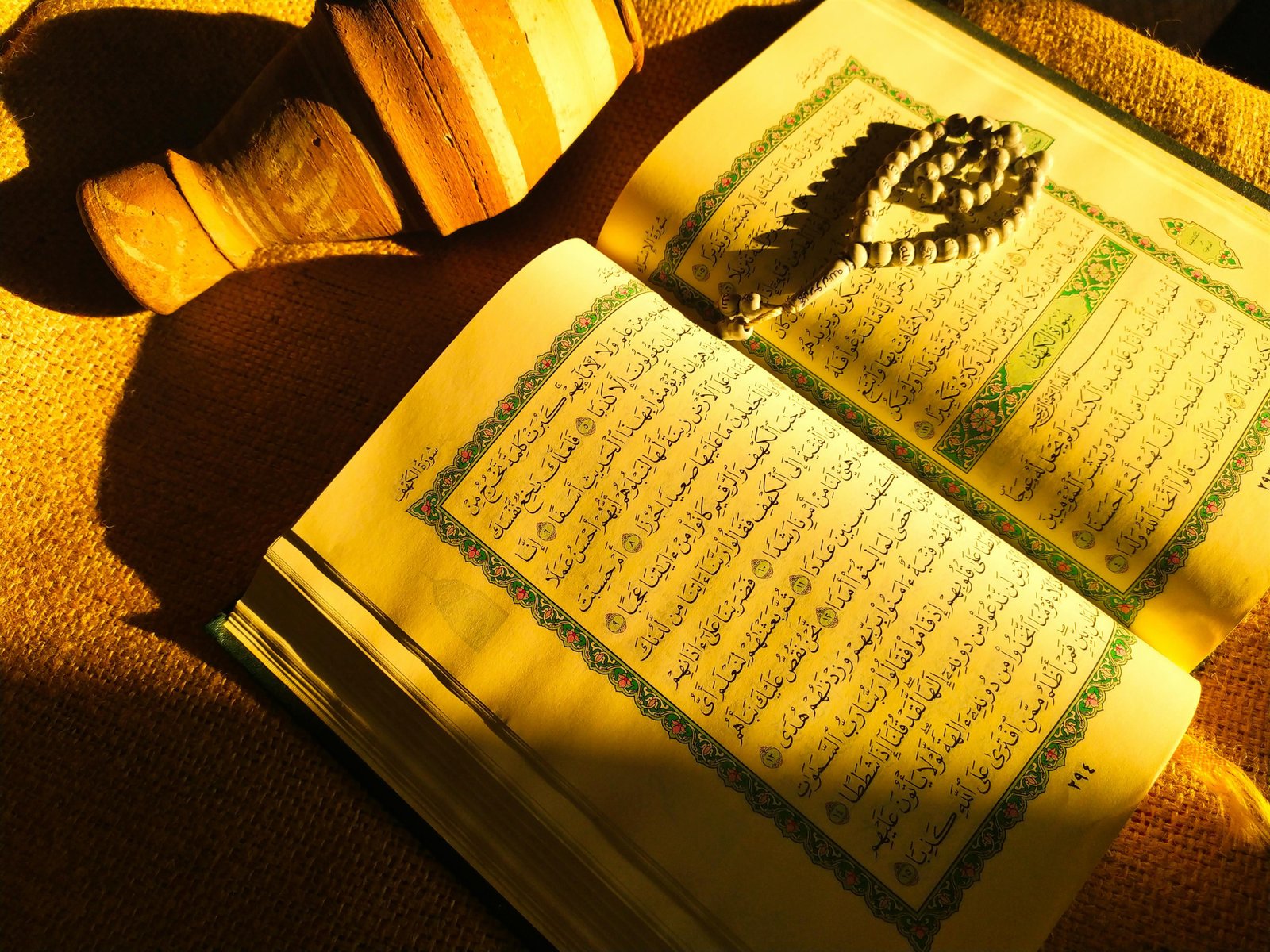

When sacred texts are discussed, faith often shields them from scrutiny. Yet history invites a necessary

and honest question: Is the Qur’an an original divine revelation, or does it rely heavily on earlier Biblical

scriptures? This question sits at the center of comparative religion, theology, and textual criticism.

From a historical standpoint, the Bible is significantly older than the Qur’an. The Hebrew Scriptures date

back to roughly 1400–500 BC, while the Qur’an was compiled in the 7th century AD. By the time the

Qur’an appeared, Jewish and Christian texts were already established, circulated, and foundational to

religious life across the Middle East.

A striking observation is that many of the Qur’an’s central narratives already existed in the Bible. Stories

of Adam and Eve, Cain and Abel, Noah’s Flood, Abraham, Moses, David, and Jesus appear in Biblical texts

centuries earlier. This overlap raises a critical question of originality: how can material documented long

before be presented later as fresh revelation?

Islam identifies many of these Biblical figures as prophets, yet introduces Muhammad as the final

prophet. This creates a theological tension. If Moses, David, and Jesus were legitimate prophets, why do

their own scriptures make no reference to Muhammad? From a critical perspective, progressive

revelation should demonstrate continuity that is historically traceable, not retroactively imposed.

Language and culture add another layer to the discussion. Moses was an Israelite born in Egypt, raised in

a non-Arabic environment, and historically disconnected from the Arabic language. Yet his story appears

in Arabic form in the Qur’an. The Qur’an itself acknowledges previous scriptures, describing its message

as a confirmation of the Book of Moses. Critics argue that this admission highlights dependence rather

than independence.

Unlike religious traditions that introduce distinct mythologies or entirely new cosmologies, the Qur’an

draws extensively from Biblical material. To skeptics, this reliance weakens claims of divine originality.

Genuine revelation, they argue, should stand on its own introducing unique theological concepts rather

than reiterating established narratives for a new audience.

This discussion is not merely theological; it is historical and analytical. Applying the same standards of

scrutiny to all sacred texts leads to an unavoidable question: Does the Qur’an function as an

independent revelation, or is it a derivative work shaped by the scriptures that came before it?

For readers willing to examine faith through the lens of history, this question remains open, and deeply

significant.

Is the Quran a New Revelation or a Reworked Message?

Timna Valley

Eliran t Via Wikimedia Commons